John Matusiak’s article on the History Press’ website succinctly appraises the situation with regard to the traditional historiography of King Henry VIII. The present writer would have included the reference to Nero in this essay’s title but John correctly and somewhat courageously used it as his book title ‘Henry VIII, The Life and Rule of England’s Nero’ (The History Press, 2013).

Academic historians of the dominant Whig school influenced generations of scholars until relatively recently. Such eminent historians as Sir Geoffrey Elton, Dr David Starkey and A.G Dickens inevitably regarded Henry as the founding father of modern England. The monarch who stood up to the foreign ‘tyranny’ of the Papacy, had the courage to implement a much needed religious reformation and revolutionised government. According to this view, Henry was a colossal figure and significant player on the European political stage, whilst simultaneously epitomising the ideal cultured, learned, humanist Renaissance prince.

Popular historians have tended to examine Henry through the prism of his colourful matrimonial entanglements and focused more on each unfortunate woman who occupied the queen’s revolving throne. This genre has given rise to a competition, akin to a popularity contest, or an early-modern ‘reality show’ portrayal of each of the women. This trope has also seen him portrayed as ‘Bluff King Hal’ – a benign figure who revelled in his hedonistic lifestyle and courted the love of his subjects. Fate and circumstances conspired against him and altered his temperament radically. Some have even attempted to play medical detective and diagnose from beyond the tomb. The king fell off his horse in January 1536 and was unconscious for a couple of hours. This was responsible for such a dramatic personality change and, by implication, his subsequent behaviour can be explained and or excused. Those of us of a certain age will find this a little too reminiscent of the cartoon character, ‘The Incredible Hulk’!

Historical novelists have perhaps been the most serious saboteurs of attempts to ascertain the truth about both Henry and those in his orbit. As the professional historian, G.W Bernard has remarked, historical novelists use their imaginations to fill in the enormous gaps in our knowledge and ‘risk embedding images that are at best fanciful and at worst, downright false’. [1]

In a similar vein, writers and bloggers skirt around the issue of the paucity of primary sources by deploying much speculation and unnecessary ‘padding’ in order to compensate for the lack of hard evidence. This is really quite irresponsible and reinforces myths and stereotypes in popular perception.

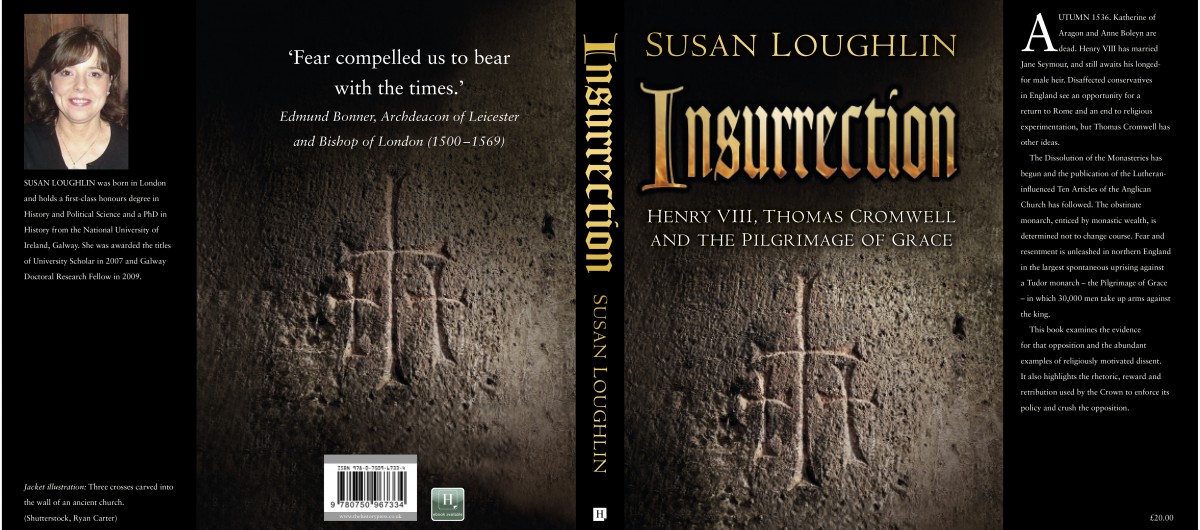

However, evidence for Henry VIII’s reign during the period of Thomas Cromwell’s ascendancy is more plentiful, thanks to the latter’s organisational skills and diligent record keeping. It is a result of this that a study of the largest of all Tudor rebellions, The Pilgrimage of Grace, 1536 can be examined in more depth by the use of primary sources. This rebellion was as much a rising against Cromwell himself as that of the king and has been the subject of much debate among professional historians.

30,000 men took up arms against Henry in the autumn and had the potential to threaten his grasp on the throne.

The way in which Henry avoided this and navigated his way through this affront to his dignity is explored in Insurrection: Henry VIII, Thomas Cromwell and the Pilgrimage of Grace. The ramifications for the protagonists and the impact on Northern society in the aftermath are also discussed by the careful examination of contemporary sources.

Henry’s behaviour throughout the rebellion was typical of his character; a character shrewdly summarised by the French ambassador, Marillac in the above title. Of the king, he said that Henry’s three prevalent character vices were avarice, suspicious nature and inconstancy’.[2]

Frequent examples abound to support Marillac’s assessment throughout the king’s reign and are highlighted in this most recent study of the Pilgrimage of Grace.

[1] G.W Bernard, Anne Boleyn: Fatal Attractions, Yale University Press, 2011, Preface.

[2] Eric Ives ‘Henry VIII: the Political Perspective’ in The Reign of Henry VIII: Politics, Policy and Piety, Diarmuid MacCulloch (ed.), 1995, p.31.

https://www.amazon.co.uk/Insurrection-Henry-Thomas-Cromwell-Pilgrimage/dp/0750967331

Have you found a way of seeing the recent Jones/ Lipscomb series on C5, Doc?

LikeLike

No, not available here. I wouldn’t mind a look at some stage.

LikeLike

I must admit I don’t find much of this surprising. When one looks at Henry’s motives and actions it seems pretty obvious that Marillac got it right. For me, Henry was a tyrant and a destructive influence on English history – one of the worst and certainly one of the most self-obsessed to sit on the throne of England.

LikeLike

Yes, Marillac’s was an apt appraisal. Henry was a poor king in a number of ways. Vainglorious, spoilt, petulant, greedy and deluded.

LikeLike